Anthony Mann, an American director, gained widespread recognition for his skill in crafting westerns and film noirs. His career is notably marked by his successful collaborations with actor James Stewart, producing some of the most revered films in the Western genre, such as Winchester ’73 and The Naked Spur.

Mann began his career in the theatre, gradually transitioning to cinema in the 1940s. His earliest films were marked by the stylistic and thematic characteristics of film noir, and his works, including T-Men and Raw Deal, are considered some of the finest examples of the genre. Mann’s themes often touched on issues of identity, morality, and the often brutal consequences of ambition.

Psychological Westerns

Mann’s approach to filmmaking was characterised by meticulous attention to character development. His protagonists, often deeply flawed, navigate their complex realities, revealing layers of emotional depth and psychological turmoil. This technique is particularly evident in films like Man of the West, where Gary Cooper’s character embarks on a violent journey of self-discovery and redemption.

Visually, Mann’s films were known for their stark and rugged landscapes that reflected the characters’ internal struggles, a technique that later became a defining feature of his westerns. His use of shadow and light, particularly in his noir films, created a strikingly atmospheric cinematic environment that added depth and tension to the narrative.

Anthony Mann’s influence on the world of cinema is considerable. His films have been celebrated by directors such as Martin Scorsese and Clint Eastwood for their strong character development and visual style. His impact on the Western genre, in particular, has been significant, with his work contributing to a shift in how the genre is perceived, pushing the boundaries of traditional narratives and character archetypes.

Anthony Mann (1906 – 1967)

Calculated Films:

- The Furies (1950)

- Winchester ’73 (1950)

- Bend of the River (1952)

- The Naked Spur (1953)

- The Far Country (1954)

- The Man from Laramie(1955)

- Men Of War (1957)

- Man of the West (1958)

Similar Filmmakers

Anthony Mann’s Top 10 Films Ranked

1. The Naked Spur (1953)

Genre: Western

2. The Man From Laramie (1955)

Genre: Western

3. Winchester ’73 (1950)

Genre: Western

4. Man on the West (1958)

Genre: Western

5. Men of War (1957)

Genre: War

6. Raw Deal (1947)

Genre: Film Noir

7. The Far Country (1954)

Genre: Western

8. The Tin Star (1957)

Genre: Western

9. The Furies (1950)

Genre: Western, Drama

10. The Tall Target (1951)

Genre: Thriller

Anthony Mann’s Frontier: From Noir Alleys to Western Valleys

Not quite John Ford, not quite Sam Peckinpah, Anthony Mann bridged the gap between two eras of Hollywood Westerns. He was an indomitable figure whose modest origins birthed an extraordinary story. Born in 1906 in San Diego, Mann was the son of an Austrian academic and an American mother. The cultural dichotomy Mann grew up in would later seep into his films, where contrasts often played out in raw and emotional drama. The family soon relocated to New York City, where Mann’s nascent interests in drama and theatre began to bud amidst the hustle and bustle of a metropolis that never sleeps.

The neon-lit Broadway stage beckoned Mann in his early twenties. But rather than bask in the limelight as an actor, Mann found his calling behind the scenes. Beginning as an assistant director and stage manager, over the years, he developed a reputation as someone who deeply understood the intricacies of drama and an ability to mine the depths of characters and extract performances that resonated with raw authenticity.

Mann’s theatre trajectory was not one of meteoric rise; it was a slow simmer. Over time, working with groups like Theatre Guild and Eugene O’Neill’s Provincetown Playhouse, he honed his directorial skills, always seeking the heartbeat of every story.

But if Broadway beckoned him, Hollywood summoned him. By the late 1930s, Mann felt the screen’s pull and relocated to the city of angels, initially immersing himself in screenwriting. However, it was his foray into television in the early years that truly broadened his directorial palette. Here, Mann encountered the challenges of narrating within constrained timeframes. Television, a medium often unfairly dubbed as the lesser cousin of cinema, was an apprenticeship for Mann. It imbued in him the skill of capturing the essence swiftly, of painting emotions in bold yet controlled strokes.

The year 1942 saw Mann transitioning fully into film direction. The early features like Dr. Broadway and Moonlight in Havana were not the pinnacle of his capabilities, but they provided an entry point for him. While marked by the trappings of their genres, these films hinted at Mann’s growing fascination with nuanced characters, with shades of grey that defied the black-and-white dichotomies.

Slowly but surely, Mann’s style began to evolve — an evolution marked by meticulous attention to detail and an increasing inclination to explore the human psyche. The war-ravaged world outside the cinema halls, with all its complexities and moral dilemmas, started reflecting in his films.

Film noir, with its shadow-laden visuals and morally ambiguous characters, seemed tailor-made for Mann. The genre exploded in the late 1940s, and Mann was perfectly positioned to take advantage of this boom, crafting dark, brooding, and intense tales. T-Men in 1947, a semi-documentary-styled crime thriller, was Mann’s entry ticket into the big league. His collaboration with cinematographer John Alton, a genius in manipulating shadows, birthed scenes that were nothing short of visual poetry.

However, it was Raw Deal in 1948 that truly stamped Mann’s authority. Here was a film where every frame, every shot was an ode to the noir aesthetics — an intricate ballet of light and shadow. Yet, it was not just style for style’s sake. Mann’s narratives grappled with existentialism, with characters often entrapped in webs of their own making.

His noir phase culminated with Border Incident in 1949, a movie that underscored Mann’s gift for blending socio-political undertones with heart-pounding drama. The gritty realism of his stories the layers of complexity within his characters, marked Mann out as a director who did not merely dabble in genres but reshaped them, moulding them in his distinct vision.

The 1950s brought forth a shift in Anthony Mann’s career. As the Film Noir genre began to lose its popularity, Mann turned towards the Western. But typical of his style, he wasn’t content just directing; he sought to redefine. The vastness of the American frontier was the perfect setting for his films, with its sprawling landscapes juxtaposed against the intimate struggles of his characters.

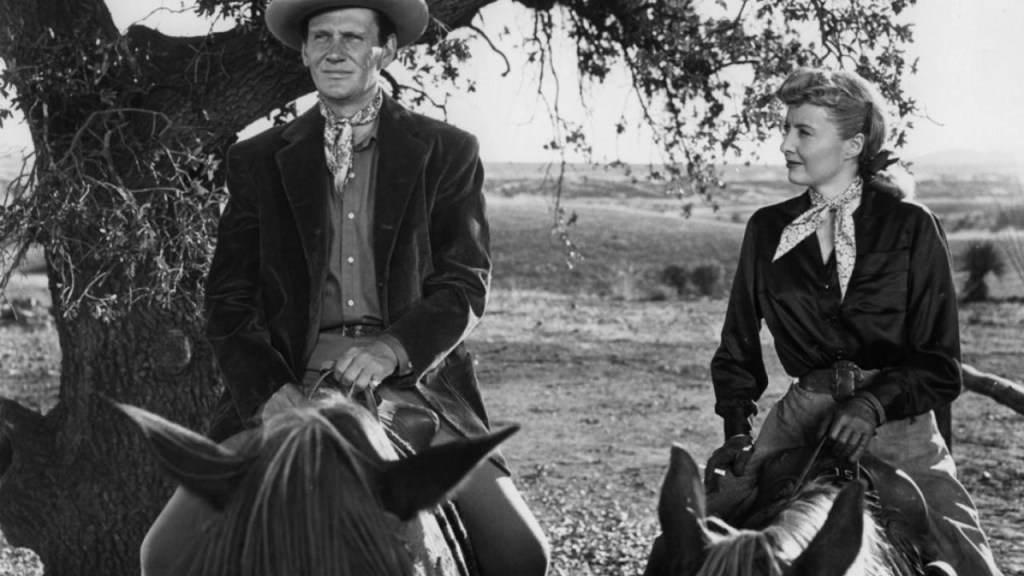

Mann’s collaboration with James Stewart, one of the most revered actors of the time, was one of the best actor-director duos ever. Beginning with Winchester ’73 in 1950, their partnership became the stuff of legends. With his everyman appeal, Stewart brought vulnerability and depth, while Mann infused these tales with his characteristic intensity.

Their collaborations birthed a slew of classics. Films like Bend of the River and The Naked Spur weren’t just about gunfights and horse chases. They delved into the psyche of the frontier man, navigating the blurred lines of morality in a world often devoid of law. Mann’s Westerns, peppered with his noir sensibilities, were a profound exploration of ambition, betrayal, and redemption.

By the time The Man from Laramie hit the screens in 1955, it was evident. The Mann-Stewart pairing had not only redefined the Western but elevated it, taking it to the realms of cinematic artistry where character arcs and moral quandaries reigned supreme.

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw Mann adapting to the times, harnessing the power of the widescreen. The expansive format was not merely a tool for Mann but an opportunity. Films like The Fall of the Roman Empire showcased his mastery of epic storytelling. The vast widescreen became a tableau on which Mann painted his narratives, meticulously choreographing grand battles while never losing sight of the intimate, personal tales unfolding within these larger-than-life scenarios.

Cimarron in 1960 was another testament to Mann’s versatility. Against the backdrop of the Oklahoma land rush, Mann told a story of ambition, love, and societal change. With its vast landscapes and bustling crowds, the widescreen format served to heighten the film’s drama, adding an epic scope to Mann’s already intricate character explorations.

As the 1960s progressed, Mann’s voice felt lost. His films no longer felt cutting edge but increasingly outdated. The Heroes of Telemark’s World War II setting and A Dandy in Aspic, which dabbled in the spy thriller genre, showed Mann’s interest in testing his limits still existed.

Though Mann was known for often dissecting the darker facets of the human psyche, his films were never devoid of hope. There was always a light, however dim, at the end of his narrative tunnels, a testament to the indomitable human spirit that Mann so deeply believed in.

Anthony Mann’s life was tragically cut short on April 29, 1967, in Berlin, Germany. He never got to have the chance for a revival in New Hollywood. You feel that he, like Robert Aldrich, could have managed to thrive in this new world. His films share many attributes with this era’s works.

In an era where directors often pigeonholed themselves into specific genres, Mann was a chameleon. He seamlessly shifted between film noir, westerns, epics, and thrillers, but his signature style was unmistakable. It was a style marked by deep emotional resonance, layered and real characters, and narratives that posed questions rather than providing easy answers.

In modern Hollywood, directors like Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan have spoken of Mann’s movies. The ripples of Mann’s work spread beyond Hollywood. Directors across the globe, from the Italian maestro Sergio Leone to the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa, and their films reveal his influence.

With their intertwining of raw emotion and cinematic brilliance, Anthony Mann’s films remain gripping watches. Whether you choose to watch The Naked Spur, The Man from Laramie or Man of the West, you know you’re in for a good time.

Most Underrated Film

Man of the West, released in 1958, is often overlooked in Anthony Mann’s repertoire, eclipsed perhaps by his more commercially successful ventures. It’s a quintessential Mann Western, delving deep into human nature, led by a charming everyman, Gary Cooper. Cooper’s portrayal of a reformed outlaw confronted with his turbulent past is brilliant.

Its gritty realism and moral ambiguities simmer perfectly throughout the film. It’s a bleak world, perhaps one of Mann’s darkest. It isn’t one of those Westerns that bolts between action sequences. Instead, its slower pace allows audiences to connect with these characters.

So why should you watch Man of the West? Simply put, it’s a brave film that offers no easy resolution or simple dichotomies but delves deep into the complexities of morality and redemption. It’s a rich portrait of the American frontier where characters are not merely heroes or villains but deeply flawed individuals seeking their place in a chaotic world. The cinematography is stunning, capturing the vastness of the Western landscape and the isolation it brings. Whether you’re a fan of classic cinema or just looking for a thought-provoking watch, you can’t go wrong with this film.

Anthony Mann: Themes and Style

Themes:

- Moral Ambiguity: Mann often placed his characters in morally complex situations where the line between right and wrong was blurred. This was especially evident in his Westerns and film noirs, where protagonists were frequently tormented by their pasts and personal demons.

- Redemption and Transformation: Many of Mann’s characters embark on a journey of self-discovery, grappling with their past mistakes and seeking redemption.

- Man vs. Environment: Mann had an uncanny ability to use the environment as a character. In his Westerns, the vast and unforgiving landscapes often mirrored the internal struggles of his characters.

- Conflict and Duality: Personal conflicts, whether internal or external, were central to Mann’s stories. He often explored the duality of human nature, where characters battled with their darker impulses.

Styles:

- Deep Focus Cinematography: Mann favoured deep focus shots, where the foreground and background were in sharp focus.

- Masterful Use of Locations: Whether it was the urban jungle in his noirs or the sprawling landscapes in his Westerns, Mann used real locations to enhance the realism and atmosphere of his films.

- Tight Framing and Close-Ups: Mann frequently used tight frames and close-ups, especially during intense drama or emotional turmoil, to draw viewers into the personal space and emotions of the characters.

- Contrasting Lighting: Drawing from his film noir roots, Mann often employed a chiaroscuro lighting technique, using stark contrasts between light and dark to highlight the moral complexities of his narratives.

Directorial Signature:

- Character Depth: Mann’s characters were multi-dimensional, with flaws, virtues, and internal conflicts. Even his villains were never one-dimensional; they had depth, motivations, and vulnerabilities.

- Narrative Intensity: His films were characterised by a relentless intensity. Whether in action sequences or dramatic confrontations, there was a palpable tension that kept audiences engaged.

- Visual Symbolism: Mann was a visual storyteller who often employed symbolism in his shots. For instance, a barren landscape might symbolise isolation, or a looming mountain might represent an insurmountable personal challenge.

- Innovative Genre Blending: While Mann could operate within the boundaries of a single genre, he was at his best when blending elements from various genres, especially film noir elements, into his Westerns, adding layers of complexity and intrigue.

Further Reading:

Books:

- Anthony Mann by Jeanine Basinger – A comprehensive exploration of Mann’s career, diving deep into his filmography and examining his influence on cinema.

Articles and Essays:

- Darkness Visible: Anthony Mann and James Stewart’s Westerns by K. Austin Collins, Criterion

- Mann, Anthony by David Boxwell, Senses of Cinema

- ‘Art and the Theory of Art’: “The Man from Laramie” and the Anthony Mann Western by Jeremy Carr, MUBI

Anthony Mann: The 172nd Greatest Director