Aleksander Dovzhenko was a Soviet film director known as one of the most important figures of early Soviet cinema. Born in Ukraine, he was a key proponent of the Soviet montage theory, and his silent film trilogy — Zvenigora (1928), Arsenal (1929), and Earth (1930) — is often cited as his most significant contribution to cinema, Earth being hailed as one of the greatest films of all time.

Themes of Ukrainian nationalism characterised Dovzhenko’s films, the struggle between tradition and modernity, and the impact of industrialisation on rural societies. These themes were presented through innovative narrative structures and poetic symbolism. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Dovzhenko’s approach to filmmaking was deeply personal and emotive, focusing on individual human experiences within the broader social and political context. This approach can be seen in Earth, where he contrasts the pastoral beauty of rural Ukraine with the harsh realities of collectivisation.

Visual Poetry

In terms of visual style, Dovzhenko’s work was unique in its lyrical and symbolic approach to Soviet montage. Rather than primarily using montage for its propagandistic potential, he used it to create emotional resonance and explore the human condition. Dovzhenko’s films often feature long, contemplative shots of nature, and his use of visual metaphor and symbolic imagery was instrumental in conveying his themes; this is evident in Arsenal, where the fragmentation and rapid pace of the montage sequences underline the chaos and brutality of war.

What makes Dovzhenko a special director is his ability to balance the political demands of Soviet cinema with his artistic vision. While his contemporaries, such as Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin, are also known for their use of montage, Dovzhenko’s work stands out for its lyrical, almost impressionistic quality. His films’ deep humanism, evocative depiction of the Ukrainian landscape, and innovative use of narrative and visual symbolism distinguish him within the landscape of Soviet cinema.

Aleksandr Dovzhenko (1894 – 1956)

Calculated Films:

- Zvenygora (1928)

- Earth (1930)

Similar Filmmakers

- Abram Room

- Aleksandr Medvedkin

- Aleksandr Ptushko

- Andrei Tarkovsky

- Artavazd Pelechian

- Boris Barnet

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Igor Savchenko

- Ivan Pyryev

- Lev Kuleshov

- Márta Mészáros

- Mikhail Kalatozov

- Miklos Jancso

- Pedro Costa

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Sergei Parajanov

- Vsevolod Pudovkin

- Yuliya Solntseva

Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Top 5 Films Ranked

1. Earth (1930)

Genre: Drama, Soviet Montage

2. Arsenal (1929)

Genre: Soviet Montage, War, Political Drama

3. Zvenygora (1928)

Genre: Soviet Montage, Fantasy, Drama, Magical Realism

4. Ivan (1932)

Genre: Socialist Realism, Drama

5. Aerograd (1935)

Genre: War, Socialist Realism

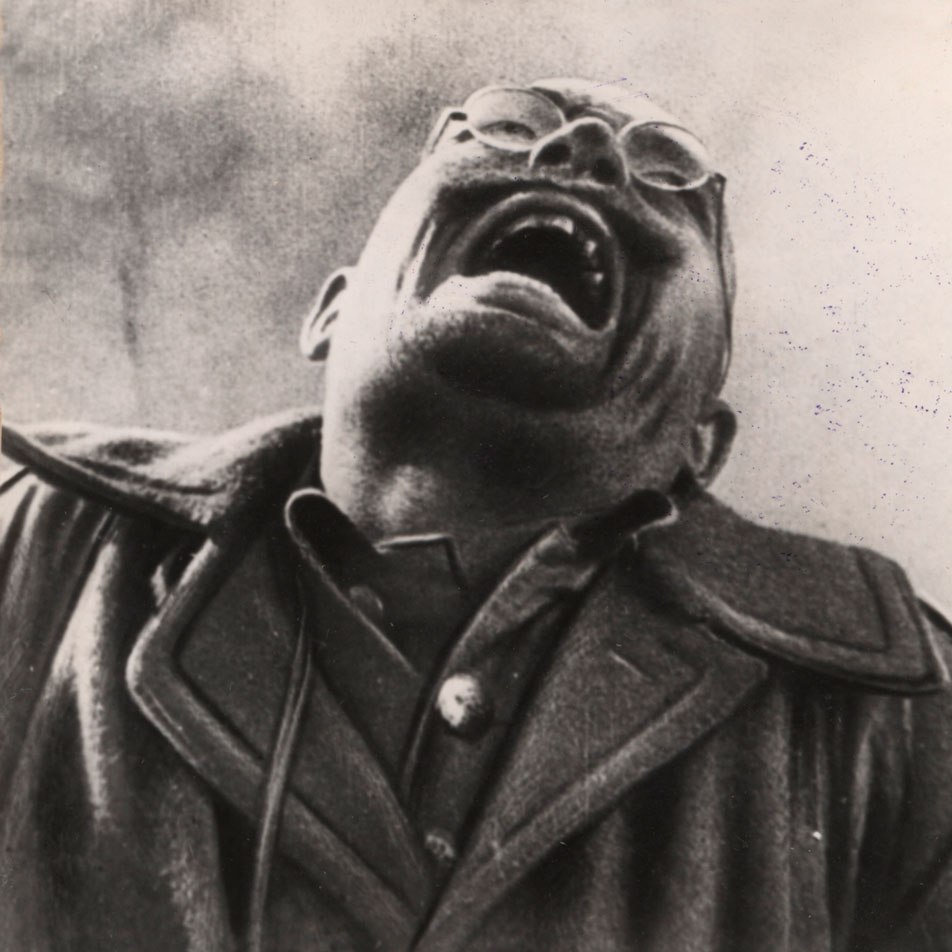

Aleksandr Dovzhenko: The Ukrainian Poet of Soviet Cinema

Among the first poets of cinema and one of the first Soviet directors to move on from montage theory, Aleksandr Dovzhenko had an uncanny ability to portray the soul of his homeland with a mix of myth, reality, and poetry. Born on September 10, 1894, in Sosnytsia, Ukraine, Dovzhenko’s early life was one of struggle and labour. Raised in a peasant family, he tasted the earth’s soil, understood its people, and grew to translate this essence into his films.

Educated as a teacher and serving in the Soviet military, Dovzhenko’s life took a turn when he was captivated by the allure of the silver screen. He quickly made a name for himself as a cartoonist. Still, he wasn’t one to rest on his laurels and sought out the new medium of cinema.

His directorial debut, Vasya the Reformer, is a lost film, but his first available film, Zvenigora, marked Dovzhenko as a major player in world cinema. A blend of folklore and revolutionary spirit, the film was a harbinger of what was to come, a glimpse into Dovzhenko’s ability to meld the old with the new.

Then came Arsenal, a film that roared with the agony and triumph of a nation in flux. Dovzhenko’s vision was unfiltered, his storytelling fierce, and his characters a reflection of the world around him.

But it was 1930’s Earth that sealed Dovzhenko’s legacy. A cinematic poem celebrating the Ukrainian land and its people, Earth was unlike anything seen before. The film resonated with truth, beauty, and a profound understanding of what it means to be connected to the land. The imagery was breathtaking, the emotions raw, and the narrative a deep meditation on life, death, and everything in between. Dovzhenko is best known for this trilogy of revolutionary films.

Sound & Onwards

In a period marked by ideological rigidity, Dovzhenko dared to transcend propaganda, crafting films that were as much about humanity as they were about politics. His work was, at times, controversial and misunderstood. Yet, the intensity and honesty of his storytelling, the lush visual landscapes, and the deep emotional resonance were undeniable.

With Ivan and Aerograd, Dovzhenko continued to push boundaries, delving into themes of industrialisation, patriotism, and the inherent struggle of human existence. His approach was never conventional, always tinged with a sense of mysticism and a connection to something greater.

Yet, a battle with censorship and artistic constraints lay beneath the accolades and triumphs. The Soviet system was both a platform and a cage for Dovzhenko, providing him opportunities while often stifling his creativity.

But the genius of Dovzhenko was never confined; it was always alive, breathing, and pulsating with the force of a visionary who saw beyond the ordinary, who felt the heartbeat of his land, and who translated it into a symphony of images and emotions that continues to resonate across time and borders. He was more than a filmmaker; he was a poet, a philosopher, and a conjurer of dreams.

The Second World War and the End of Dovzhenko’s Career

As Stalinism tightened, so did the Soviet director’s creative leash; Dovzhenko found his opportunities limited. Ultimately, the Second World War was the end of any hope for Dovzhenko’s career. But that didn’t mean he halted.

Ukraine in Flames and Victory on the Right Bank Ukraine continued his Ukrainian-set nationalist films even if they were essentially propaganda. Dovzhenko’s keen eye and compassionate heart were evident in every frame, making these films not just historical documents but also works of art.

In the post-war years, Dovzhenko was afforded few opportunities. However, rather than succumbing to despair, Dovzhenko channelled his energy into new avenues. He turned to literary pursuits, penning novels and essays reflecting his deep intellectual curiosity and commitment to his artistic ideals.

Dovzhenko’s later years were marked by a transition into mentorship and pedagogy. As a teacher, he nurtured a new generation of filmmakers. He instilled in them the skills of the craft and the spirit of creativity, the pursuit of truth, and the courage to push boundaries.

Influence on Soviet Cinema

His influence was global, resonating far beyond the Soviet Union. Filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Parajanov drew inspiration from Dovzhenko’s unique blend of poetic realism and humanism, seeing in his work a path to a more profound understanding of cinema’s potential.

Even in his twilight years, Dovzhenko never ceased to be a force for innovation and integrity. His final years showed his enduring passion and relentless pursuit of artistic excellence, culminating in the creation of the Dovzhenko Film Studio.

Aleksandr Dovzhenko passed away on November 25, 1956, but his legacy continues. He was a maestro who danced to the rhythm of his homeland, a director who saw the world with fresh eyes, and a visionary who transformed cinema into an experience that was spiritual, cerebral, and intensely human.

There were others who used the visual medium of cinema to make poetry, but Dovzhenko was perhaps the first to truly elevate the art form by blending it with national identity, nature, and human emotion. His lyrical imagery and symbolic storytelling live long after every person captured in his celluloid has passed.

Most Underrated Film

Is it really a surprise that every Aleksandr Dovzhenko film is underrated nowadays? He is a dead director who made movies in a dead nation. So many of his colleagues are no longer even talked about in cinephile circles; arguably, it’s just him, Eisenstein, Kalatozov, and sometimes Boris Barnet left. As the march of time sweeps away the dust of history, his groundbreaking trilogy – Zvenigora, Arsenal, and Earth – has become obscured.

Like the ephemeral beauty of a setting sun, these three films linger in the periphery, waiting to be rediscovered and appreciated anew.

Zvenigora, the first in this masterful trilogy, is a tapestry of myth, history, and revolution. A tale woven with the threads of Ukrainian folklore and modern sensibility, it’s a film that transcends time, a cinematic poem that sings of a land’s soul.

Arsenal follows with its stark and unyielding portrayal of a nation in turmoil. Its bold expressionism and visceral intensity make it not just a film but a battle cry that echoes the pain, rage, and hope of a people caught in the throes of change.

Finally, Earth is a film that is perhaps the epitome of Dovzhenko’s artistic vision. It’s a celebration of the land, a meditation on life and death, a visual symphony that speaks to the very core of human existence. These films, Dovzhenko’s magnum opus, deserve to be seen and explored once more.

Aleksandr Dovzhenko: Themes & Styles

Themes:

- Nature and the Land: One of Dovzhenko’s recurring themes is his celebration of the land and nature. This is perhaps most vividly realised in Earth, where he explores the spiritual connection between the land and the people who inhabit it.

- Revolution and Change: Dovzhenko’s films often grapple with the idea of revolution and societal transformation, reflecting the tumultuous times in which he lived. Arsenal is a stark portrayal of revolution and the struggle for change.

- Myth and History: Merging myth with history, Dovzhenko created a tapestry that connects the past with the present. Zvenigora is a prime example, where he weaves Ukrainian folklore into a modern narrative.

- Human Existence and Condition: His films explore the deeper aspects of human existence, from the celebration of life to the contemplation of death. He often portrayed the human condition in all its complexity and contradiction.

Styles:

- Poetic Realism: Dovzhenko’s films are noted for their poetic realism, blending stark, honest depictions of life with a lyrical and often dream-like quality.

- Visual Innovation: His films are characterised by innovative visual techniques, including pioneering uses of montage and juxtaposition. The visual composition is often symbolic, adding layers of meaning.

- Emotional Intensity: Dovzhenko’s films are emotionally charged and filled with raw intensity. He did not shy away from portraying human emotions in their most unfiltered and powerful form.

- Narrative Complexity: The complexity of narrative structure in Dovzhenko’s films allows for multifaceted storytelling. He often interweaves different time periods, perspectives, and themes.

Directorial Signature:

- Symbiosis with Nature: Dovzhenko’s love for nature and the land is not just a theme but part of his directorial signature. His films breathe with the rhythms of nature, creating a sense of harmony and symbiosis.

- Bold Experimentation: His willingness to experiment with form, narrative structure, and visual language made him a true innovator. His films are both reflective of their time and ahead of it.

- Humanist Approach: A profound humanism is at the core of Dovzhenko’s work. He saw cinema as a means to explore and understand the human soul.

- A National Voice with Universal Appeal: While deeply rooted in his Ukrainian identity, Dovzhenko’s work transcends national boundaries. His voice is both distinctively national and universally resonant, making his films accessible and meaningful across cultures.

Further Reading

Books:

- The Poet as a Filmmaker: edited by Marco Carynnyk – A detailed examination of Dovzhenko’s cinematic style and thematic concerns.

Articles and Essays:

- Dovzhenko, Aleksandr by Jeremy Carr, Senses of Cinema

- Subversions in Dovzhenko’s Earth by Romana M. Bahry, Harvard Ukrainian Studies

- Re-examining Dovzhenko’s Political Environment: A Response to Riley by George O. Liber, Film Philosophy

Aleksandr Dovzhenko – The 241st Greatest Director